The Feel of a Word: scrub

The word scrub is related to the word shrub and in England referred to a brushwood or undergrowth. It could also be a coppice or copse where the trees were grown to a certain height and then cut down for use. But in Australia the scrub is totally natural, mostly despised, and ranging from above human height to a low heath. The nature of the scrub is dependant on the soil type, the predominant vegetation and the rainfall. Scrub usually occurs on poor soil so that the plants are stunted. It can be thick or thin, close or open, but, if the former, it is so matted and overlapping that it is impenetrable.

In the early days of the colony scrub was interchangeable with brush, both of them being distinct from forest or bush which was more open. The following quote from Tegg’s Monthly Magazine in 1836 makes that point:

On the banks of rivers the bush changes its character very materially, for in these situations, instead of the open forest in which you can trot along briskly among the lofty trees, it becomes a sort of impenetrable jungle, or as the colonists term it, a thick brush.

This is in accord with Grace Karskens observations about the Hawkesbury:

What sort of forest grew on the banks of the Hawkesbury-Nepean River? Here is what an early surveyor Charles Grimes scribbled in his field book: “thick brush”. “brush”, “scrub”. But what did these words mean? Settlers used words for vegetation in different ways from us. Brush referred to what we now call rainforest, or other forests where the undergrowth of shrubs and vines was so dense that moving through it was difficult. Some brushes were well-known landmarks, such as “North Brush” at present-day Eastwood, Bargo Brush south-west of Sydney and, of course, “Curryjong Brush”.

Mostly what settlers wanted to do with scrub was to get rid of it, as the following account in The Wells of Beersheba makes clear:

Old McShane’s selection, where he lived quite alone, was in the middle of the Big Scrub, twelve hundred acres of belah and brigalow, forty feet high and as thick as the hair on a heeler’s back, fair in the middle of ten thousand acres of the same class of country. ‘He’ll have a fine place some day – if he ever gets the land cleared.’ That’s what people said of him, practical people who had selected in open forest county, or, at most, had selections that were part forest and part scrub.

The Big Scrub was an area of subtropical rainforest near Lismore in NSW, dominated by the booyong and the red cedar.

Clearing scrub was easier said than done. Mallee scrub, for example, had deep lignotubers, roots with water held within them, that defied attempts to remove them until they were attacked with steam tractors dragging scrub rollers.

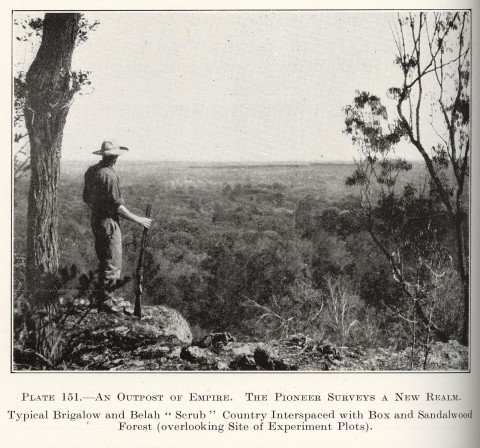

Scrub was often identified as being typically a particular type of plant, so we had the brigalow scrub, the belah scrub (form of casuarina), the wattle scrub, the tea-tree scrub. Just to break the pattern the area covered by wallum (a type of banksia) was known as the wallum lands. Just as scrub becomes the scrub, the name of a particular tract of land covered by scrub, so did we acquire the brigalow, the pindan, the mulga.

Ludwig Leichhardt gave a public lecture on his explorations which was reported in the Melbourne Argus of 1846. Leichhardt uses the name bricklow for the acacia which he encountered on the Darling Downs. This is possibly the earliest anglicised form of the Kamilaroi word burigal. The Kamilaroi lived in the area of the Liverpool Range in New South Wales, extending into Queensland. The brigalow belt or brigalow country refers to this region west of the Dividing Range.

Leichhardt said:

Not only the high level land west of Darling Downs, which sloped almost imperceptibly to the south-west, but the valleys of the rivers and the sides of the mountains were covered with extensive scrubs principally composed of a species of acacia, which has received the name of bricklow from the squatters ... This shrub or small tree has a foliage of greyish green colour, and grows so close that it is impossible, or only with the greatest difficulty, that a man on horseback can make his way through it.

So the brigalow was pretty but Leichhardt later remarks that it made it impossible to keep track of cattle. This was a common situation, that cattle and horses would escape into the scrub to lead a precarious existence in the wild. A scrub bull was to be feared because it was leaner, meaner and stronger than your average bull and appeared out of nowhere, vision being so limited.

Pindan is from the Bardi word bindan, Bardi being the language spoken in northern Western Australia, north of Broome. As is the way with many of these terms, we begin with the name for the characteristic vegetation. The name pindan was applied to a number of types of acacia but in particular to Acacia tumida, also known as pindan wattle or spear bush (from its use in making spears and boomerangs). It is a small many-stemmed shrub of a sprawling nature found in the tropical semi-arid regions of northern Australia. The seeds are edible. Like the brigalow it has a habit of growing in dense clusters so that the thick vegetation is then referred to as pindan and finally the whole area characterised by this vegetation is called the pindan.

Bushmen prided themselves on their ability to take a line of sight when entering the scrub and hold to it even in the thickest part where vision was so limited. Getting lost in the scrub was not a pleasant experience.

Our view of scrub is probably still essentially negative and our immediate reaction is still to want to clear it out and cut it down.