The Feel of a Word: skiting

Making yourself out to be better than you are by way of boasting and showing off is something that Australians have never tolerated. We have had different words for this behaviour at different times of our history but they have always been words that convey a scathing disapproval.

Skiting is a colonial word that, for Australians, was a shortened form of blatherskite, a Scottish dialect word. Its origins go back to two Scandinavian words, Scotland having always had a strong connection to the North. Blather or blether is an Old Norse word for stupid talk and skite is from the Old Norse –skyt, the stem of skjota to shoot. So a blatherskite is someone who shoots his mouth off, so to speak, tossing random nonsense out endlessly. This early citation is from Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 1847 in a comment on cockfighting:

D.P. begs to call the most particular attention of the cockers … to this, as he has been informed that there has been a good deal of blatherskiting lately about the Swamp. The sooner the battle comes off the better, especially as there is so much money about.

The reference to the Swamp is possibly to the Gumbramorra Swamp, the site of present-day Marrickville and Petersham which is where the poor of Sydney mostly lived at that time.

In Australian use we found it amusing to split blatherskite into the phrase blather and skite which made it easier for us to end up with skite on its own. This is an early example:

You may blather and skite,

But electors won’t bite

At the bait that,

On Friday, you threw so.

So now, Mr Francis,

You’ve led us some dances,

But never again

Will you do so.

The Herald (Melbourne), 1872.

This example is a fairly late one:

We were told a short time ago that the sleeper service was to be restored but Federal Minister Ward, head sherang of the blather and skite department, told Mr O’Sullivan that he another think coming. As a result railway travellers are still sleeping on bags …

Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative, 1945.

It is interesting that both are political gibes. The random foolish talk became more specifically empty boastfulness, the equivalent of bullshit, that other favourite Australian word.

In the early 1900s a new slang expression was to have tickets on someone, meaning that you had a strong liking for someone. A citation in 1908 is to do with a man speculating on whether a girl has tickets on him or not. If you have tickets on yourself you like yourself a lot! The theory is that this comes from gambling, from horseracing in particular where you put money on a horse and are given betting tickets. There are also examples of its use in boxing. One boxer is accused of liking himself for a win so much so that he must have got tickets on himself or set up his own book. It has been suggested that the expression could have come from mannequins in shop windows, which at that stage had every item ticketed for price, or from lottery tickets. But the overwhelming context of the early use is gambling as this early citation from the Brisbane Courier makes clear:

A youngster contemplated his big sister, the other day, and wished to express contempt for her self-appreciation: -- ‘Sis doesn’t think much of herself!’ he said. ‘Oh, no! She’s only got twenty tickets on herself!’ He had evidently been studying the totalisator method.

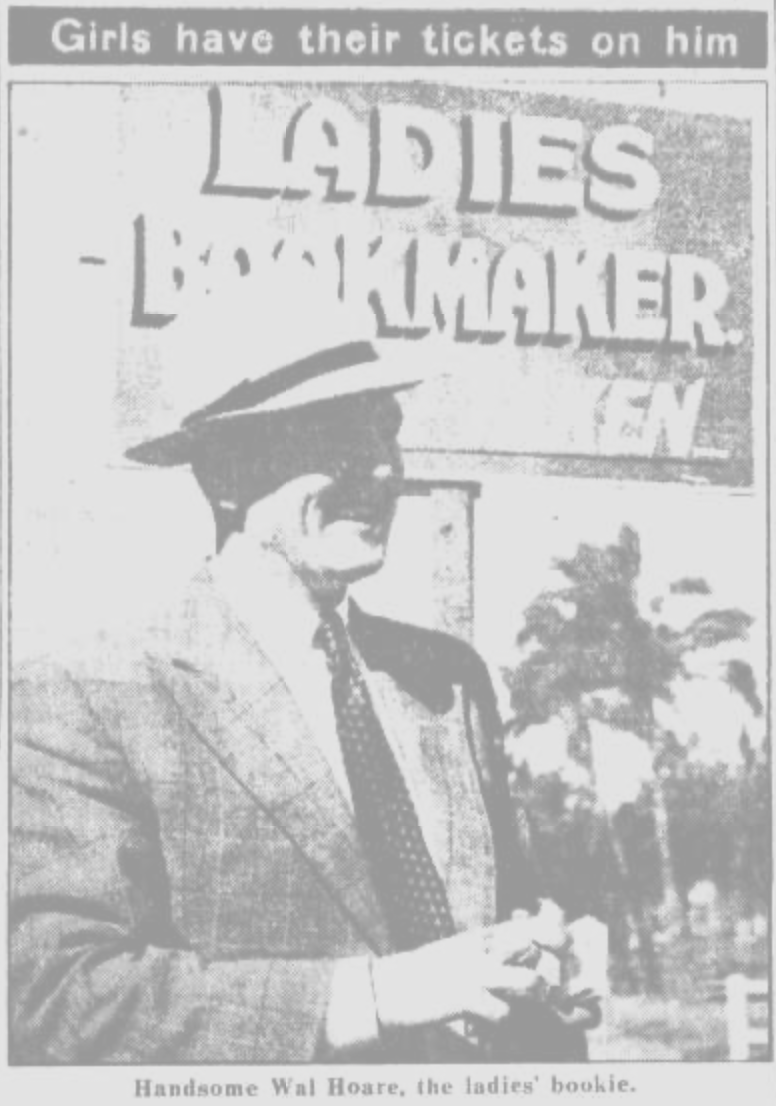

By 1947 it was possible for a headline writer in the Sun (Sydney) to make a play on both meanings of the phrase. The headline ran:

Girls have their tickets on him

The story was about Handsome Wal Hoare, the ladies bookie. He favoured female punters because he said they were much more accepting of losses and easier to deal with. In return the women found him more engaging. So they had tickets on him, meaning they liked him and they got their betting tickets from him as well.

From fancying yourself, in the betting fashion, it is an easy step to being boastful and vainglorious, which is the sense that survives today. Perhaps the gambling origin is why for so long it was only men who had tickets on themselves. Women would use the phrase but only to describe men. By the 1980s this had levelled out and the phrase could be applied generally.

So we move on to 1940s slang and the expression to big-note oneself. This also comes from gambling and refers to the person who bets big notes on a horse. At the stage the higher denomination notes were bigger than the lower ones, so a tenner was a bigger note than a fiver. A big-noter was seen to be splashing his money around and making a show of his wealth.

The expression generalised quite quickly so that, outside of the world of betting, it was possible to big-note by showing off in all sorts of ways. By the 1980s the showing off was restricted to a verbal trumpeting of one’s powers although there is still a sense that the big-noter belongs in the world of money, power and influence.